Introduction:

A loan refers to the act of lending something, typically in the form of money, to another party. Loans can be extended by friends, family, or various financial institutions and private companies.

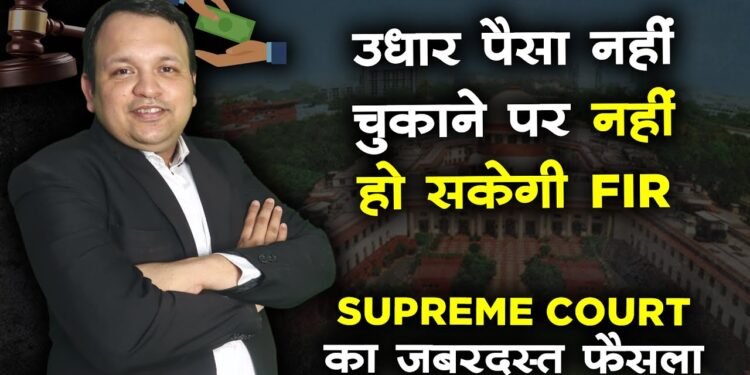

Loans are a common financial arrangement between a lender and a borrower. However, sometimes, unforeseen financial difficulties can prevent the borrower from repaying the loan. This doesn’t necessarily imply bad intent on the borrower’s part; it could be circumstantial. In such situations, what recourse does the lender have? Can they file a criminal suit? What if the borrower has no malicious intent? Can the lender involve the police, and is an FIR (First Information Report) justifiable? We’ll address these pressing questions, so read on.

Or if any confusion arises, feel free to contact us through;

Landmark Judgement of Satishchandra Ratanlal Shah v. The State of Gujarat (3 January 2019)

Brief facts of the case:

Satishchandra Shah had borrowed Rs. 21 lakh from a company with a one-year repayment period. While he had repaid a portion of the loan, he found himself unable to settle the remaining amount due to financial instability. When the company learned of this, it issued a notice to Satishchandra Shah, which he was unable to honor due to his financial condition. Importantly, he asserted that his inability to pay was not due to any malicious intent but rather his circumstances.

In response, the company initiated two legal actions: a civil suit for recovery and a criminal suit involving Section 406 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), which deals with “criminal breach of trust,” and Section 420 of the IPC, which relates to “cheating.” Both a civil suit and an FIR were filed against Satishchandra Shah.

Satishchandra approached the Gujarat High Court, filing a petition under Section 482 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CRPC) in 1973. This section grants the High Court the inherent power to challenge the maintainability and validity of an FIR. According to Satishchandra, the matter was essentially a civil dispute and should not involve criminal proceedings. Despite the charge sheet being filed, the High Court did not intervene and dismissed the petition.

Dissatisfied with the High Court’s decision, Satishchandra eventually appealed to the Supreme Court, challenging the High Court’s dismissal order under Section 482 of the CRPC.

Satish Chandra’s primary arguments were as follows: he had no malicious intent, having repaid a substantial portion of the loan. He asserted that his situation amounted to a breach of contract rather than a breach of trust. Furthermore, the company had already initiated a civil suit against him.

The company’s legal team contended that Satish Chandra Shah had harbored malicious intent to evade repayment from the outset. They argued that this warranted the continuation of the FIR.

Final Judgement:

After careful consideration of both parties arguments and a review of previous judgments, the Supreme Court delivered its decision, focusing on three key points:

1. Continuity:The Court noted that the complainant (the company) had engaged in numerous transactions with Satish Chandra, who had fully repaid his dues in the past. This established that they were familiar with each other and indicated a lack of malicious intent on Satish Chandra’s part.

2. Law of Pleadings: The Court emphasized that since a civil suit had already been filed against the respondent and Satish Chandra had provided a written statement in response, the criminal court (the police) lacked the authority to investigate the matter, as the civil court was already handling it. Disputes related to financial matters were not suitable for conversion into FIRs.

3. Breach of Contract vs. Criminal Breach of Trust: The Supreme Court made a crucial distinction between a breach of contract and a criminal breach of trust. It stated that when a contract or agreement’s terms are violated, the typical recourse is a civil suit. A criminal breach of trust comes into play when malicious intent, such as cheating, is evident from the beginning of the agreement or contract. Given the known relationship between the parties, previous transactions, the ongoing civil suit, and partial payment, the case was primarily a breach of contract. Consequently, Sections 406 and 420 of the IPC were deemed inadmissible, and the FIR was quashed.

Conclusion:

This case underscores the complexity of loan-related legal matters. Loans can be extended by friends, family, or financial institutions, and unforeseen circumstances can hinder repayment. In the case of Satishchandra Rattanlal Shah v. The State of Gujarat (3 January 2019), the Supreme Court’s ruling clarified that when parties have a history of transactions and the borrower’s inability to repay is due to genuine financial constraints, it typically falls under the breach of contract rather than criminal breach of trust. This judgment serves as an important precedent in loan-related disputes where there’s a lack of malicious intent.

To understand such complex laws in simple ways, stay connected with www.thelegalshots.com .

If doubts persist, contact our Legal Experts at